There is little doubt that the area known as Pea Ridge in Union County, South Carolina, was a rough-and-tumble place. This was especially true in the 1800s. Theft, assault, lynching, murder. Many God-fearing men of the Ridge left their morals behind at the church door when they had a wrong to avenge.

In the area known as Pea Ridge, in the last weeks of 1861…

… Seaborn Woolbright murdered Mastin Comer.

WHO WAS SEABORN WOOLBRIGHT?

In legal documents, his name spelled Seaborn, Seaberry, Sebron, Seebern, Cebron. He was one and the same, a man whose name confused many. I will use SEABORN in this work.

Seaborn Woolbright was born about 1835. I have not put in the hours of research needed to find his father’s name. There is no doubt that he was of the family line headed by Barnabas Woolbright.

Barnabas Woolbright was in Union County by 1800. His name was recorded in legal documents as Barnabus, Barney, Barnett, and other variations. He is found in Union County SC census records in 1800, 1810, and 1820, His estate settlement was initiated in 1828 and managed by Capt. J.F. Walker.

After settling debts and expenses, his widow received $60.66 and each of ten legatees received $13.53, as documented in court records dated January 3, 1831.

Jesse Woolbright was a son of Barnabas Woobright and one the the ten legatees, as was Betsy, wife of Timothy Haney, then living in Tennessee.

Jacob Woolbright was also a son of Barnabas. This is known because distributions from the estate were made on February 12, 1833, to Mary Austin, Dickson Lumpkins (for his wife Sophia Woolbright), Robert Hays (for his wife Elizabeth Woolbright), and Sally –all heirs of Jacob Woolbright.

Seaborn Woolbright would have been a grandson of Barnabas Woobright, although I have not documented this. Should you research this Woolbright family, be forewarned that there were multiple generations of men named Barnabas Woolbright in South Carolina, Georgia, and Alabama.

Seaborn Woolbright was the son of Milly Foster. Although I have seen no solid documentation, there is good circumstantial evidence.

Milly Foster (b. 1811) was the daughter of Virginia born James “Bully Jim” Foster (1784–1854) and his wife Jane (Jinny) Foster (1786-1864).

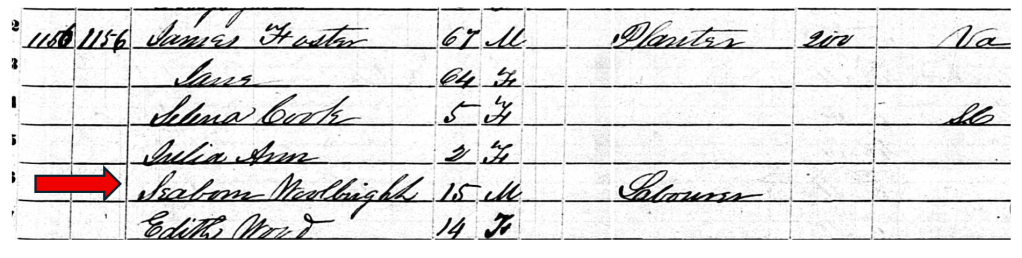

Seaborn Woolbright, age 15, was in the 1850 household of his presumed maternal grandparents, James and Jane Foster. This home was in the Pea Ridge/Kelton area of Union County.

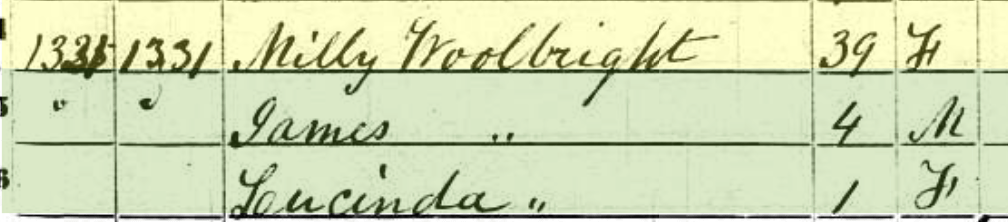

In 1850, Milly Foster Woolbright was head of household near Grindal Shoals, at the Pacolet River. Four-year-old James Woolbright and one-year-old Lucinda Woolbright were in the home. If these children were genetic Woolbrights, then her Woolbright husband had died by 1848/1849 or had deserted the family by 1850.

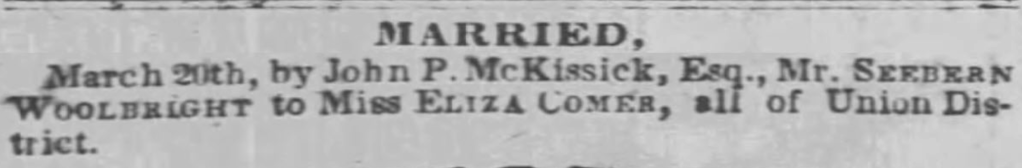

Seaborn Woolbright married Louisa Eliza Comer on March 20, 1859.

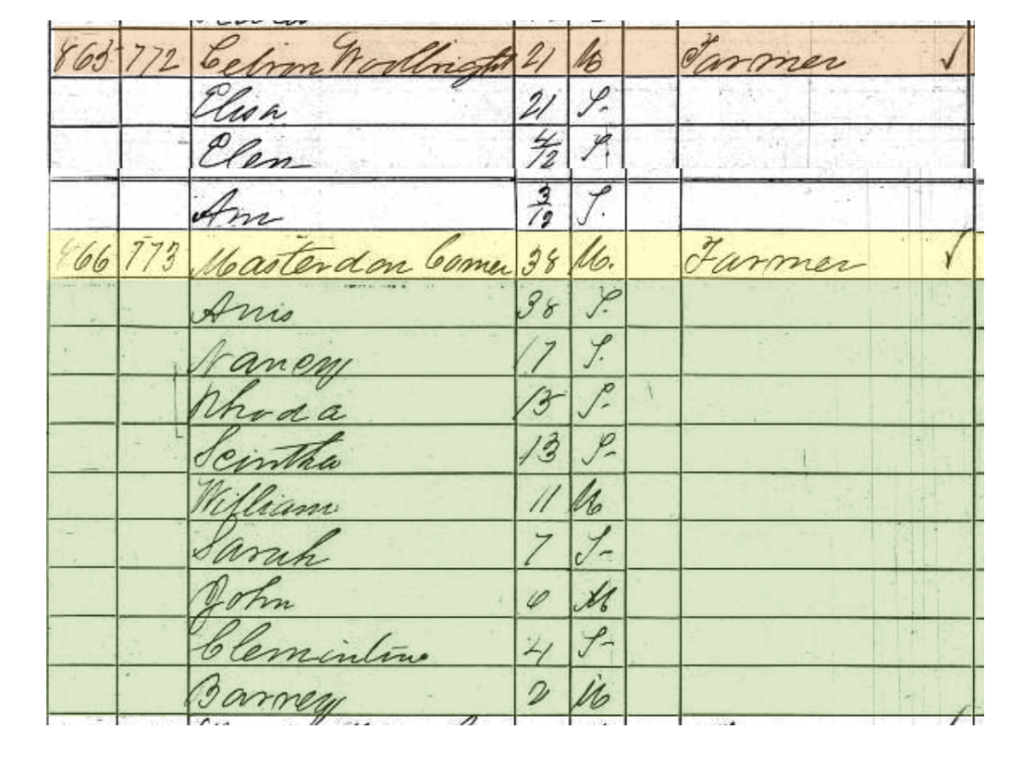

In 1860, Seaborn Woolbright was in the household with his wife Eliza Comer and their two infant daughters.

The head of household in the home next door was none other than Masterdon Comer. AKA Mastin Comer. Father of Louisa Eliza Comer. Father-in-law of Seaborn Woolbright. Soon to be murder victim of — yes, his son-in-law — Seaborn Woolbright.

WHO WAS MASTIN COMER?

Mastin Comer was born about 1822 in Union County SC. He was the son of William Comer (1774–1838) and Nancy Porter (1781–1865). He descends from the Comer, Haney, Jeter, Porter, and Palmer families — all solid stock who came from Virginia and other parts unknown. These families were foundation settlers in the Pea Ridge section of Union County. Their descendants still live there today.

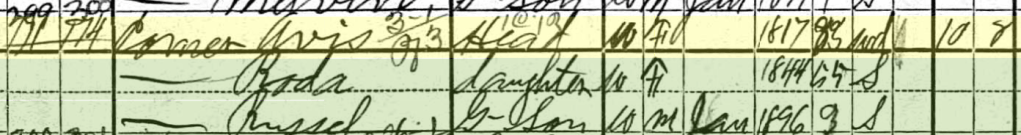

Mastin Comer married Avis Gregory (1824-1902), daughter of John Gregory (b. ca. 1800). The 1910 census confirms that they had ten children during the marriage.

Louisa Eliza Comer, born about 1839, was the first of the ten children. Her marriage to Seaborn Woolbright would eventually lead to the death of her father.

THE MURDER

It is known that five or six weeks before January 6, 1862 and most definitely before December 10, 1861, Mastin Comer, his son-in-law Seaborn Woolbright, and Jedithan P. “Gid” Porter were walking in the public road near the Porter home.

There was an argument between the father-in-law and his son-in-law. Harsh words escalated into blows. The fight ended when a knife was brandished and the younger man plunged it into the skull of the elder.

Mastin Comer did not fall to the ground and perish. If he fell to the ground, the gravely injured man pulled himself back up, perhaps assisted by Jedithan Porter. Did he stagger home or was he carried to his bed?

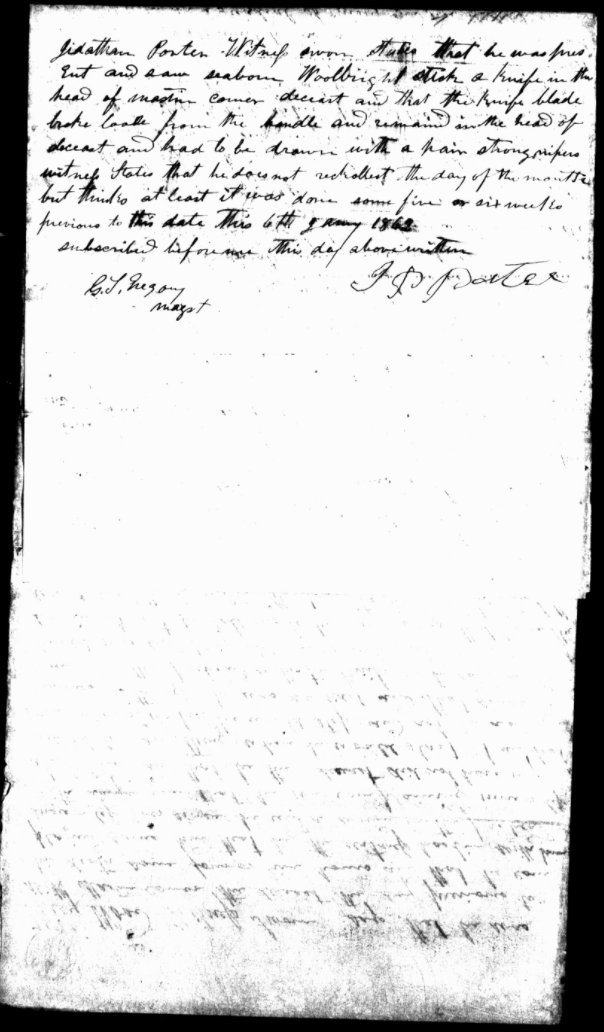

Jedithan Porter was the only witness to the horrible affair. He would later swear he was there when Seaborn Woolbright stuck a knife into the head of Mastin Comer.

The force of the attack caused the knife blade to break loose from the handle; the blade remained in the skull of Mastin Comer. It took a firm hand and a strong pair of nippers to pull the blade out of the injured man’s head.

THE FRIEND

Wiley Wood was a neighbor of the Porter, Woolbright, and Comer families. It can be said that he was a friend of Mastin Comer. The two men were about the same age. If I dove deeply into my research, it is possible that I would even find they were related. These people on the Ridge intermarried often and everyone was practically related in some way.

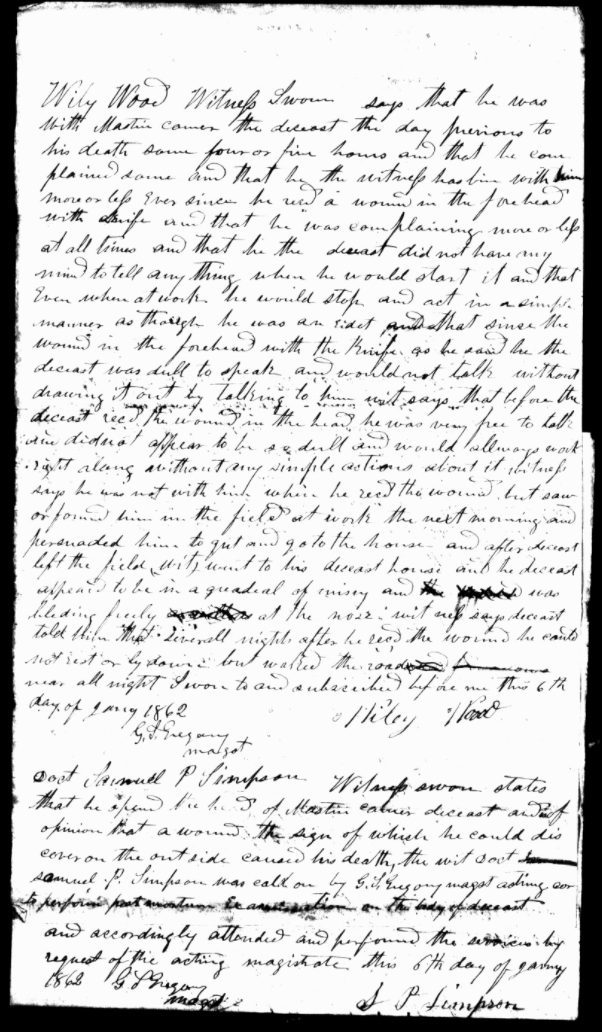

Wiley Wood was not present the day Mastin Comer was attacked. Instead, he found his friend the next morning at work in the field. Concerned about the state in which he found him, he convinced Mastin Comer to stop work and go home. He went later to the Comer home and discovered the injured man in great misery and bleeding from his nose.

Wiley Wood had spent a lot of time with Mastin Comer in the years previous to the attack. He knew Mastin Comer had spoken easily and worked tirelessly in the fields alongside him before the knife had been plunged into his forehead.

Wiley Wood did not forsake his friend. He was with him from the day he found him working injured in the field until the day before his death. He noticed that Mastin Comer had become idiotic. His speech was dull, and he complained constantly. He was described by Wiley Wood as being “simple’ and unable to finish his thoughts.

If Seaborn Woolbright held the knife in his right hand when he struck Mastin Comer in his forehead, the blade would have entered the left frontal lobe of his brain.

This part of the brain — in particular Broca’s area — is crucial for speech production, articulation, and grammar, allowing us to form words and sentences. Damage to this area would have caused Mastin Comer’s struggle to speak fluently.

He told his friend Wiley Wood that he was not able to lie down or rest for several nights after the attack, and he walked the roads at night

.I do not know if medical help was ever sought. I am not in the medical field so what I am about to say is speculation. My guess is that Mastin Comer suffered a slow brain bleed until his death; or the wound became infected from a dirty knife blade and he went into septic shock. I do not know if doctors in that day and age had the medical knowledge to help poor Mastin Comer. It was a slow death.

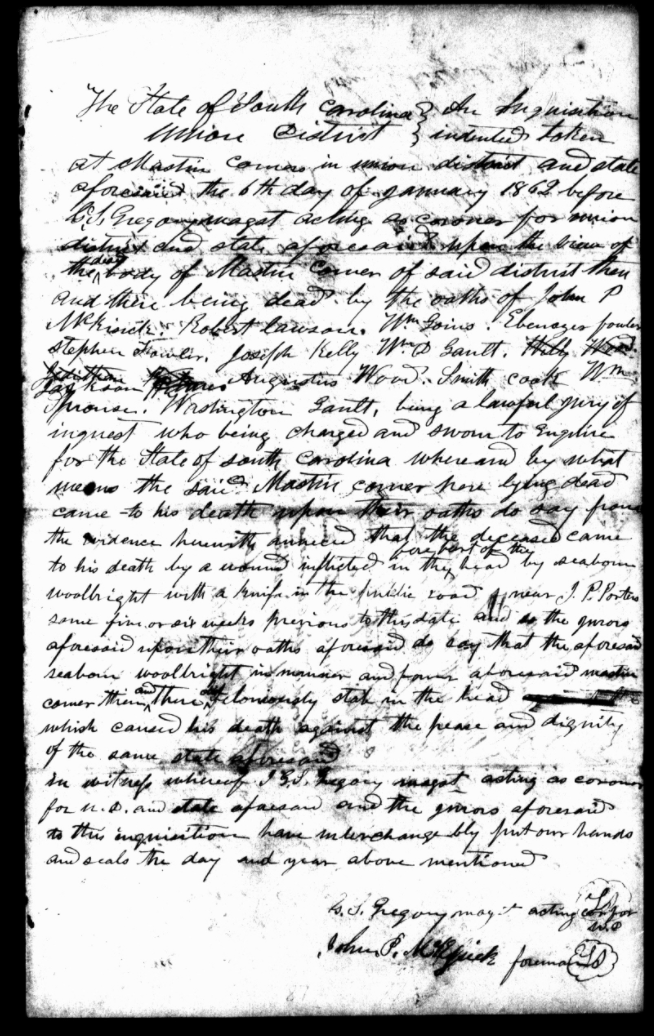

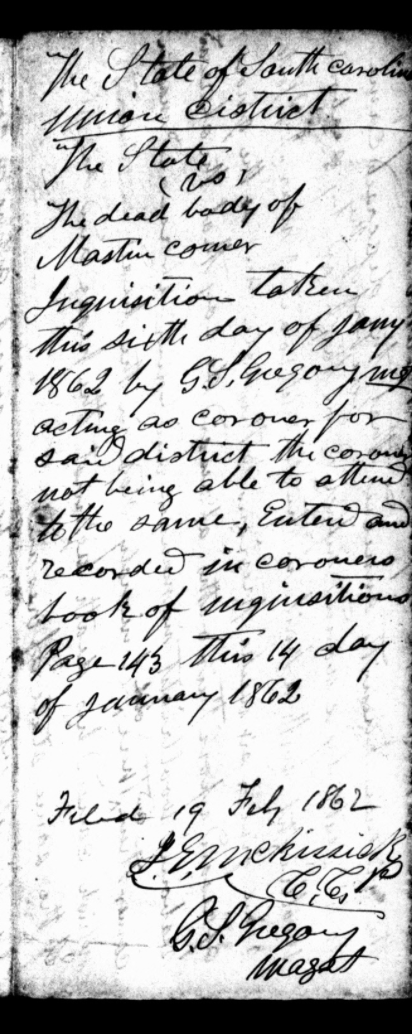

THE CORONER’S INQUEST

The exact date that Seaborn Woolbright stabbed his father-in-law is unknown. I estimate that the attack occurred between November 23 and December 9, 1861.

Since the Coroner’s Inquest was held over the body of the deceased, it is known the suffering of Mastin Comer ended and he went to meet his Maker by January 6, 1862.

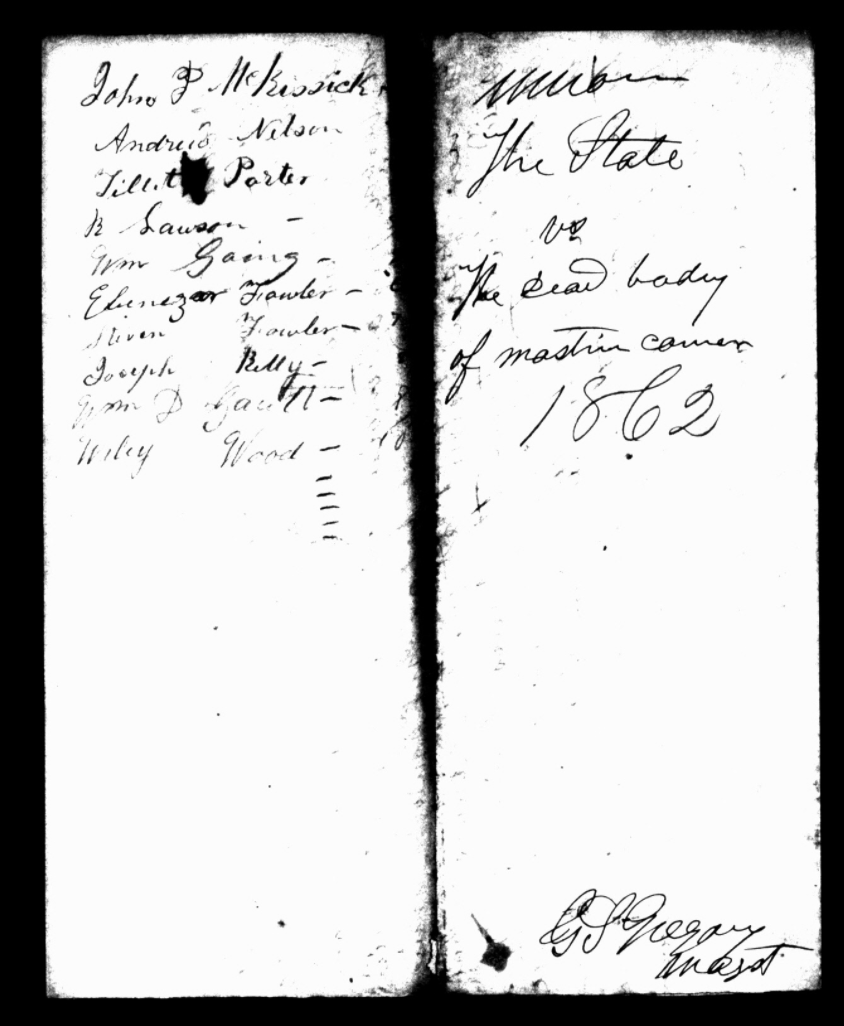

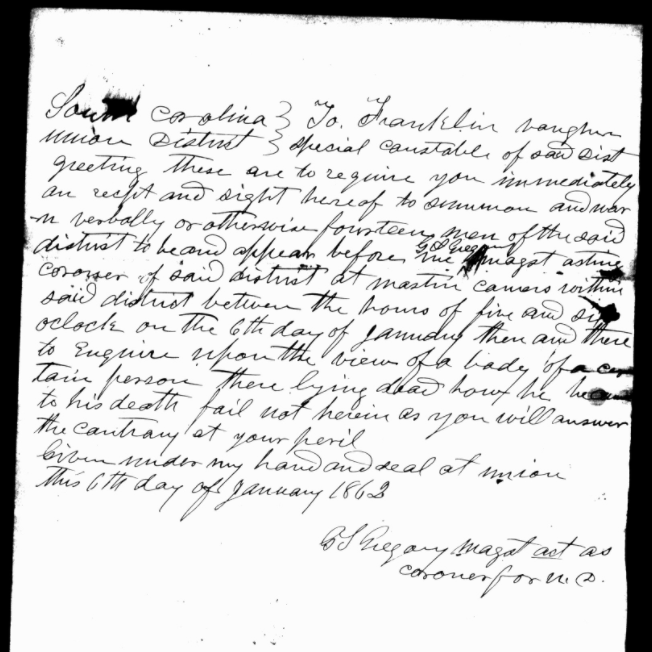

Summons signed by Magistrate G.S. Gregory were issued to special constable Franklin Vaughn. He was to notify the jury to be at the home of Mastin Comer between 5 and 6 o’clock on January 6, 1862.

G.S. Gregory served as Coroner at the Inquest.

Three men were called to testify:

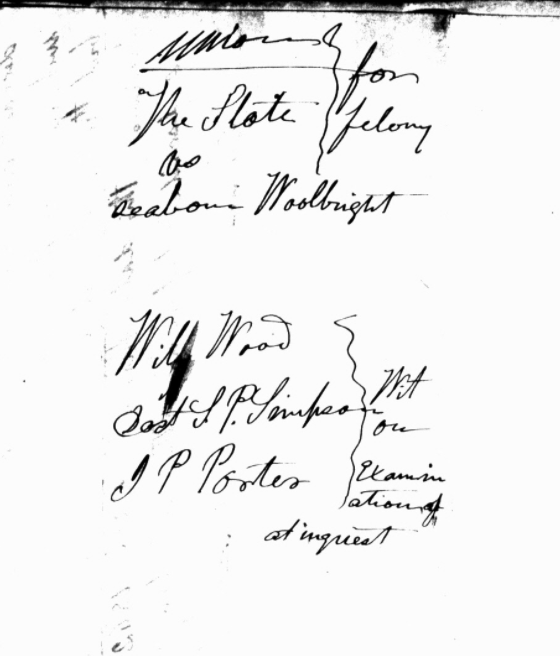

Jedithan Porter was an important witness at the Inquest. His presence during the attack gave great weight to the evidence he presented as he described what had happened that day.

Wiley Wood’s sworn statement of Mastin Comer’s behavior since the attack was solid evidence in the proceedings. He had spent four of five hours with Mastin Comer the day before his death.

The third witness was Dr. Samuel P. Simpson who had been asked to perform an autopsy. He swore that he opened the wound on the head of Mastin Comer during the postmortem examination. It was the opinion of the doctor that the death of Maston Comer was caused by the wound to his head.

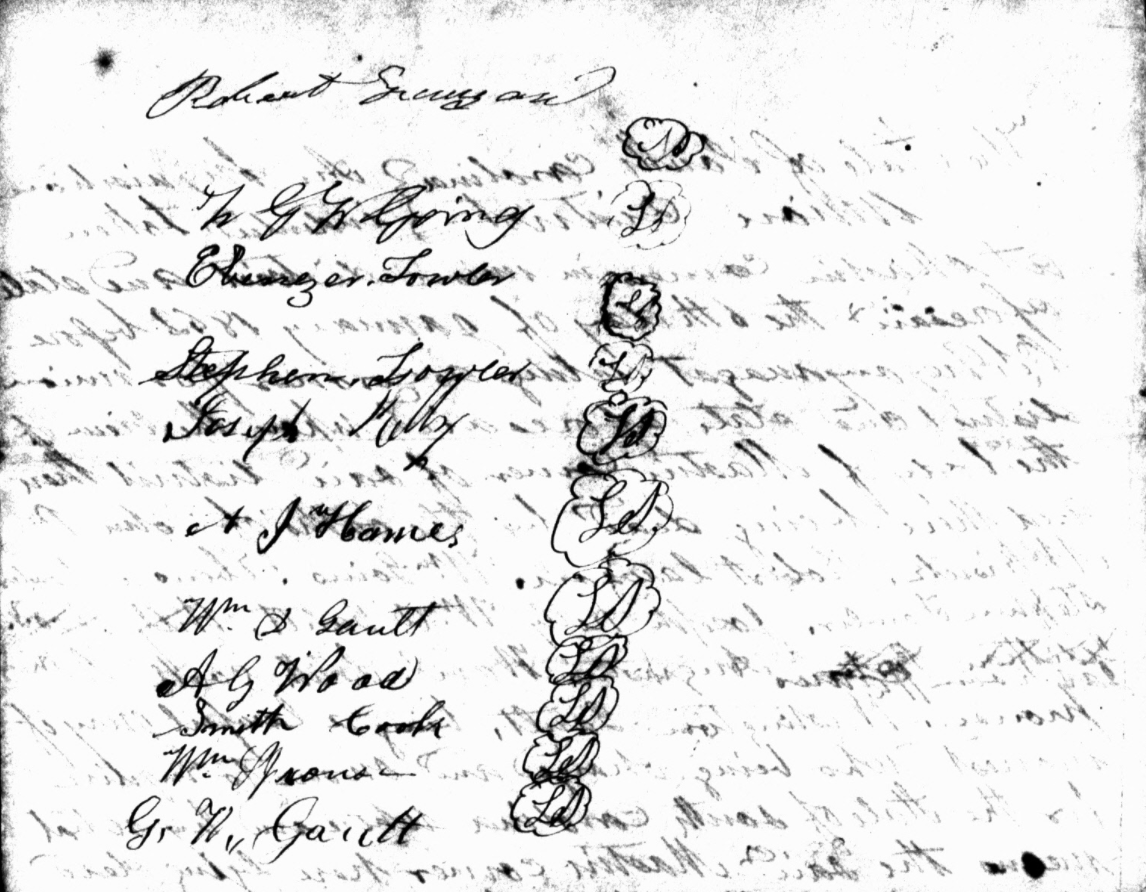

The twelve men on the Coroner’s Inquest Jury:

- John P. McKissick

- Robert Lawson

- William George Washington Going

- Ebenezer Fowler

- Stephen Fowler

- Joseph Kelly

- William. D. Gault

- Jackson Hames

- Augustus G. Wood

- Smith Cook

- William Sprouse

- G. Washington Gault

The lawful Jury headed by acting Coroner G.S. Gregory determined that Mastin Comer died from the knife wound in his head inflicted by Seaborn Woolbright in the public road near the Porter home. The attack occurred five or six weeks before January 6, 1862, the date of the Inquest.

Seaborn Woolbright would be brought to trial for felony murder of Mastin Comer.

A COLLECTION OF LEGAL DOCUMENTS

THE TRIAL THAT NEVER HAPPENED

Recognizance bonds were issued by the state on January 25, 1862 for witnesses needed to testify in court which would be held on the first Monday in March, 1862.

The men who were ordered to be in court or risk forfeiture of their bonds are listed below:

- Robert Lawson

- Ebenezer Fowler

- Jedithan P. Porter

- John McKissick

- Dr. Samuel Simpson

- Wiley Wood

- William George Washington Going

- Joseph Kelly

- Smith Cook

- G. Washington Gault

- E. F. Vaughn

In addition to the three who gave sworn statements, most men on the witness list were the same men who had been on the Inquest Jury finding Seaborn Woolbright responsible for the murder of Mastin Comer.

In the end, it would not matter. There was a Civil War going on. Soldiers were dying on battlefields far from home, and dying in droves from disease in makeshift army hospitals.

There were women and children left at home to fend for themselves. If they were lucky, they had the help of men too old and boys too young to march off to war.

Food shortages — shortages of many of life’s necessities — left both soldiers and their families back at home facing hunger and countless other hardships.

Seaborn Woolbright would never face the consequences of his actions. He was far removed on the sixth day of January 1862 when the jury composed of his neighbors decided he should be tried for murder.

The war, and lack of a defendant, made a trial for murder a worthless pursuit. There was no more mention of a trial.

It was done.

Yes, Seaborn Woolbright had killed a man, the father of his own wife. And then, he was sent to kill others with the blessing of the Confederate Calvary.

MARCHING OFF TO WAR

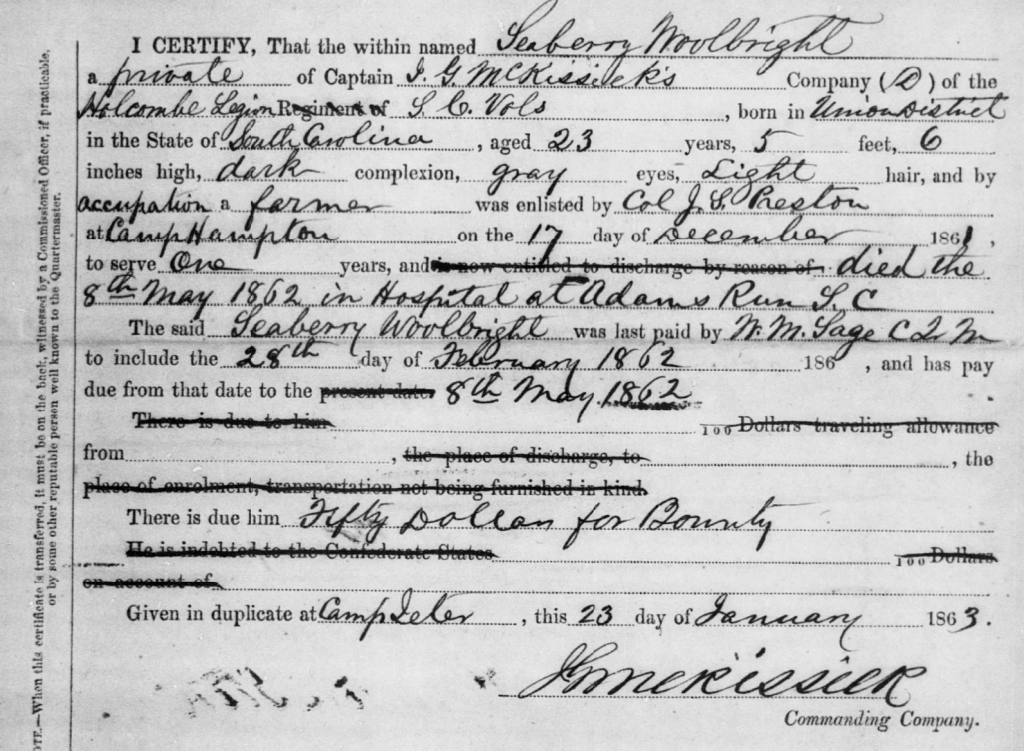

On December 10, 1861, Seaborn Woolbright –his name is “Seaberry” in military records — enlisted in the Holcombe Legion Cavalry, Captain Isaac G. McKissick’s Company D of the South Carolina Volunteers. He was mustered into service a week later, on December 17, at Camp Hampton.

He was 5’6″ tall; dark complexion, gray eyes and had light hair. His horse was valued at $125, and his tack at $20.

Did Seaborn Woolbright join the Confederate Army due to a sense of duty to the great Southern Cause, or was he attempting to escape punishment for his murderous deed? We may speculate, yet we will never know the truth.

Many of the Pea Ridge men who enlisted in this military unit did so on either December 10 or December 14, and all were mustered into service on December 17, 1861. This fact sways my opinion: Seaborn Woolbright had already planned on joining his friends, relatives, and neighbors in military service before the attack on his father-in-law.

The Civil War lasted 4 years.

Seaborn Woolbright did not.

Seaborn Woolbright was “present” in the January/February Muster Roll Call; “present, sick in camp” and “died May 8” in the March/April Muster Roll Call.

It was done.

THE DEATH OF SEABORN WOOLBRIGHT

Seaborn Woolbright died May 8, 1862 in the Confederate hospital at Adam’s Run, near Charleston, South Carolina. His only possessions at the time of his death were a few sundries and a wallet containing twenty dollars.

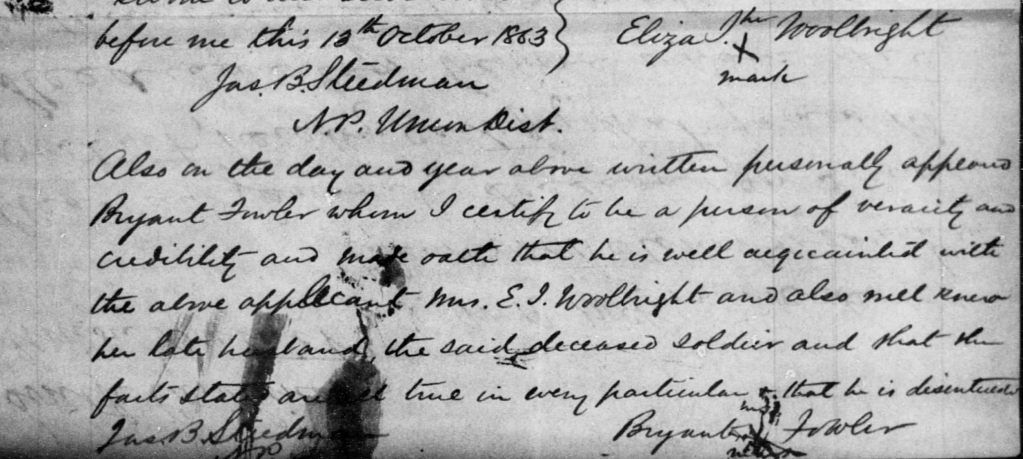

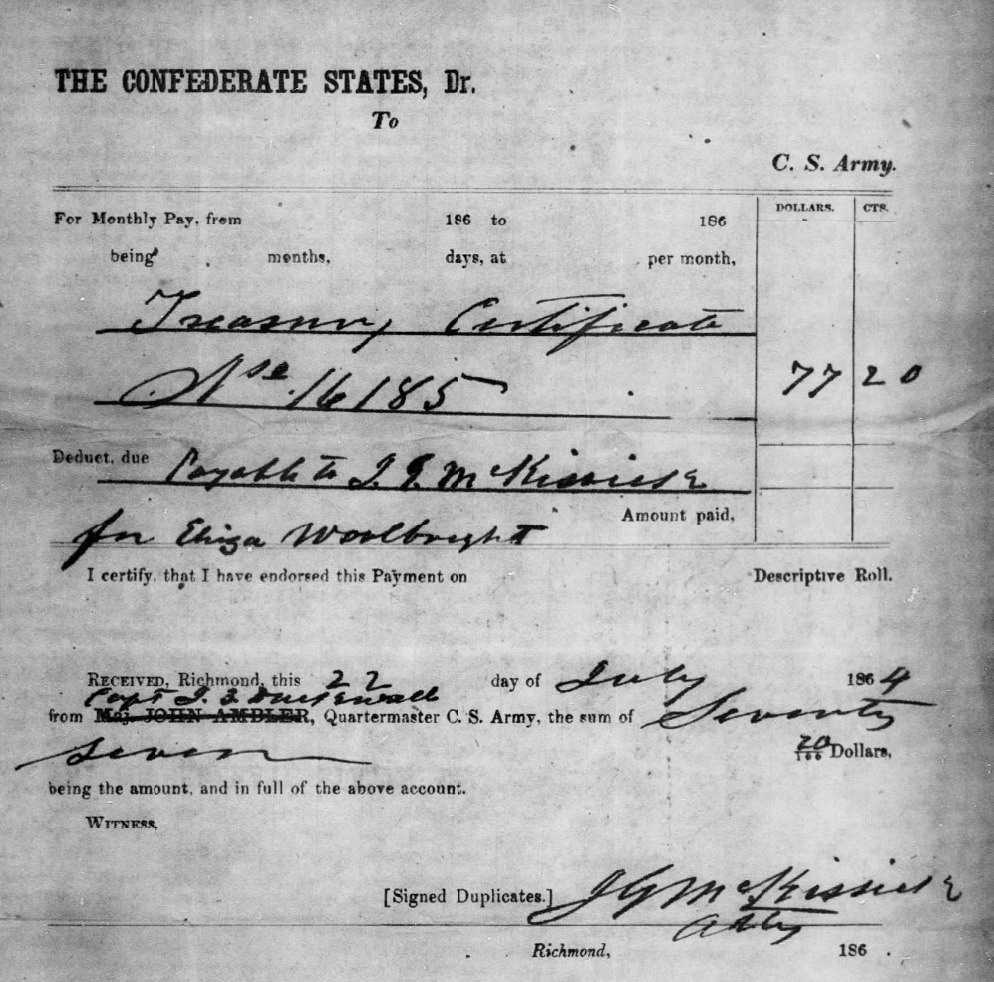

James B. Steadman and Bryant Fowler (son of Stephen Fowler) signed a document that helped the widow Louisa Eliza Comer Woolbright prove her marriage to the deceased soldier, Seaborn Woolbright. The document was signed October 14, 1863.

The widow Louisa Eliza Comer Woolbright was paid $77.20 which included a bounty payment of $50 and the balance due for the use of her husband’s horse. Captain Isaac G. McKissick represented her in the collection of the monies due to her as the survivor of her husband Seaborn Woolbright.

THE AFTERMATH

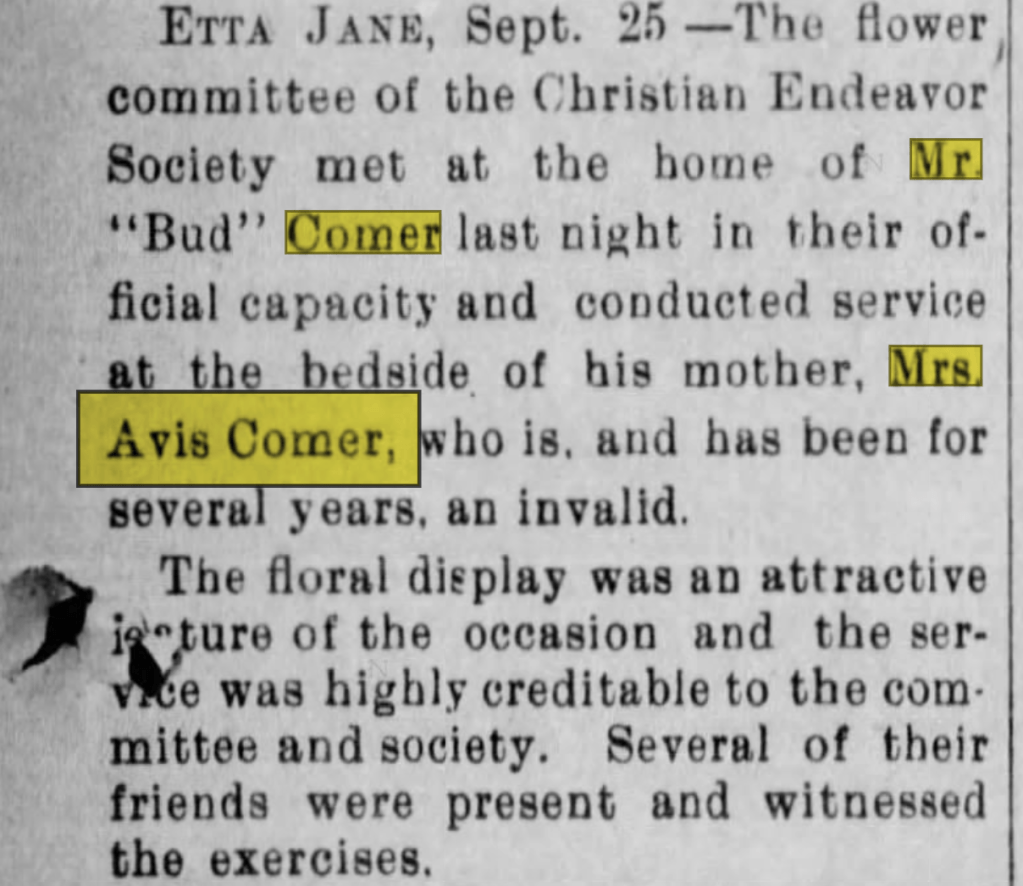

AVIS GREGORY COMER

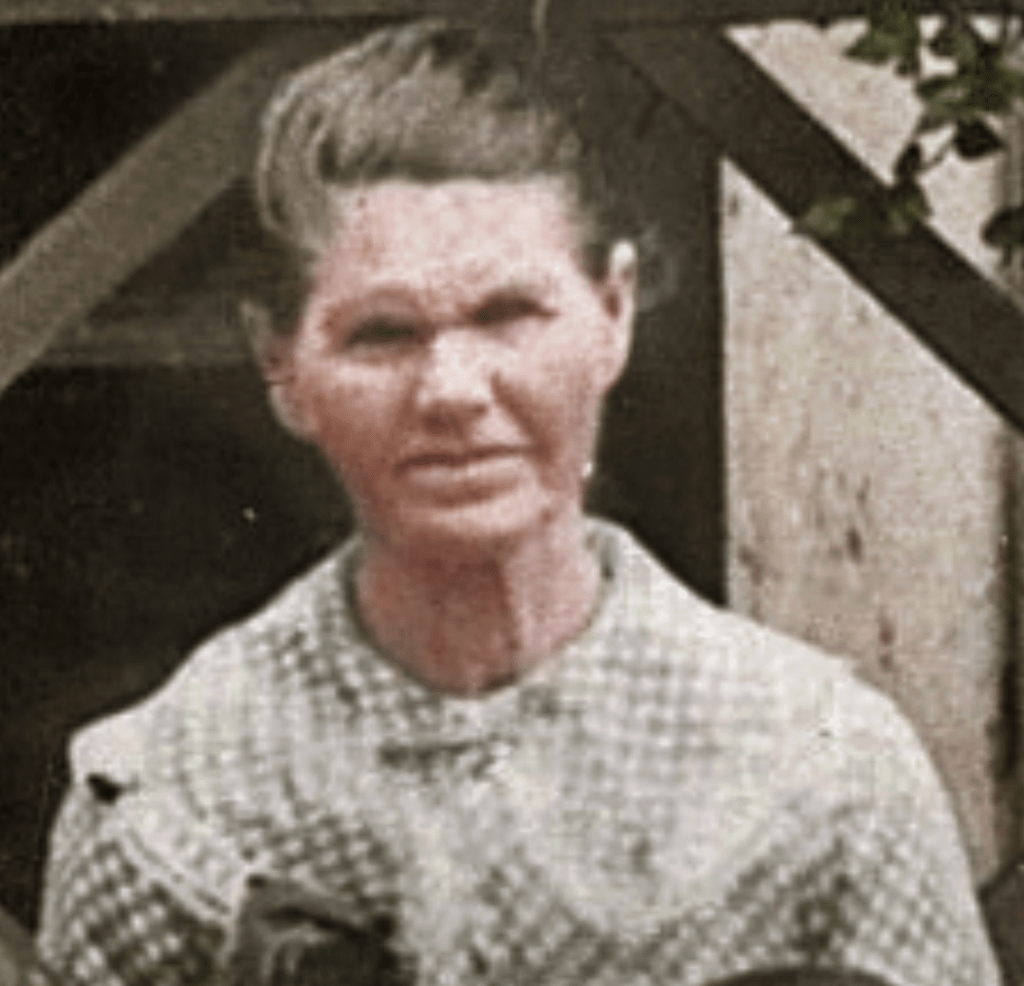

Avis Gregory Comer lived forty more years after the murder of her husband Mastin Comer. She never remarried, and lived most of her life with her youngest daughter Rhoda.

Avis Comer was an invalid for several years before her death. She died after September 1901.

LOUISA ELIZA COMER

After her husband Seaborn Woolbright’s death in 1862 in a Confederate post hospital, Louisa Eliza Comer Woolbright was left with two young daughters to raise. In 1866, she became the second wife of John W. Wright (1822-1905). She and John would have at least three children together.

Lousia Eliza Comer Woolbright Wright died in the mid-1880s.

John Wright had married Nancy Alman (1817-1865) about 1840. Nancy died in 1865. After the death of Louisa Eliza Comer, he married his third wife, Elisabeth Hames (1832–1902).

ELLEN WOOLBRIGHT

After the 1893 death of her husband Ellis Jackson Fowler, Ellen Woolbright married Lewis “Luke” Bullock (1865–1931).

Ellen Woolbright died October 20, 1935.

THE FOWLER FAMILY CONNECTIONS

My Fowler relatives are found in the middle of these families in Union County census records. It is a fact that Henry Richard Fowler (1825-1885) pulled out the eye of Wiley Wood. (I told you this was a rough-and tumble place).

Is is not surprising that there were many connections between the Woolbright and Comer families and my Fowler family.. They were neighbors. They were also related through blood and marriage.

I will start with the most obvious connection. Ellen Woolbright was born March 16, 1859. She was the daughter of Seaborn Woolbright and Louisa Eliza Comer. It was her father who killed her maternal grandfather.

Did she remember her father? It is doubtful. She would have been only two and a half years old when he joined the army and left home forever.

Ellen Woolbright married Ellis Jackson Fowler. He was born on March 15, 1854, the son of Ellis Fowler (1803–after 1860) and Jane Hodge (1826– after 1870).

Ellis Fowler was the son of “Big” Mark Fowler (1780-1853) and Elizabeth Moseley

(1782–1883). Mark Fowler was the son of Henry Ellis Fowler (1746-1808).

Jane Hodge was the daughter of John Jackson Hodge (1802–1882) and Martha Patsy Fowler (1809–1872). Martha Patsy Fowler was the daughter of Womack Fowler (1785–1849) and Susannah Moseley (1792–1878). Womack Fowler was the son of Henry Ellis Fowler (1746-1808).

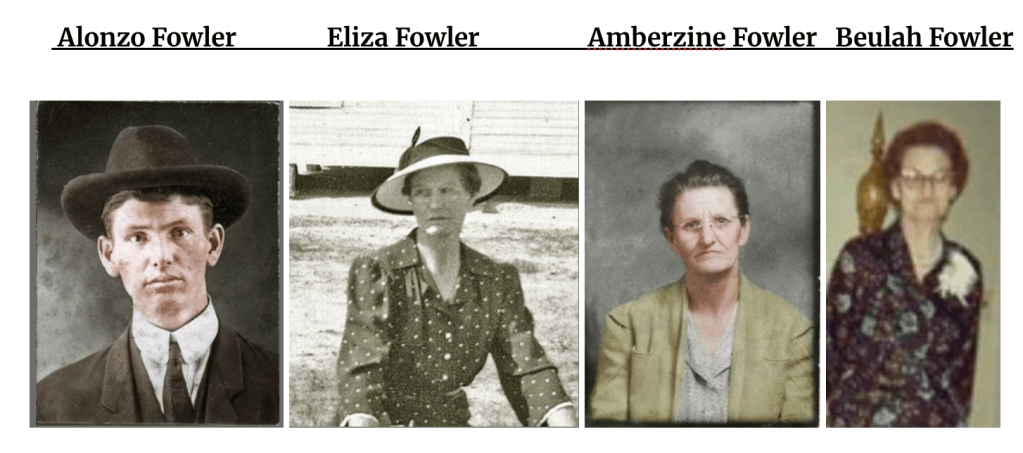

The children of Ellen Woolbright and Ellis Jackson Fowler:

- Arthur Fowler (1879–1895)

- Robert Smith Fowler (1881–1935)

- Walter Alonzo “Lonnie” Fowler (1883–1920)

- Eliza Fowler (1885–1964)

- Letha Fowler (1888–)

- Anna Amberzine Fowler (1890–1968)

- Beulah Fowler (1892–1970)

- Beatrice Fowler (1894–1900)

all photos of the Ellis Jackson Fowler family are from the collection of Josh.

A link to my work on Ellis Jackson Fowler:

Do you remember when I mentioned the name of Louisa Eliza Comer Woolbright’s second husband, John W. Wright? Again, after the death of Louisa, he married Elizabeth Hames.

Elizabeth Hames. Daughter of John M. Hames (b. 1791) and Sarah Fowler (1790-1870). And Sarah Fowler was the daughter of Ephraim Fowler (1786-1808), son of Henry Ellis Fowler (1746-1808).

And that’s not all. Elizabeth Hames was married two times before her marriage to John Wright. Her first husband was James Eaves (b. 1818) with whom she had three children.

The second husband of Elizabeth Hames was a Fowler. I have not found the first name of this man, but there is no doubt in my mind that he would have been a cousin. Two daughters were born of this marriage, Pollie Ann Fowler in 1872, and

Sallie Fowler in 1873.

The marriage was short, ending in divorce in a time when divorce was not common.

And, there is more.

Louisa Eliza Comer and John Wright had a daughter named Minnie Wright born in 1873.

In about 1890, Minnie Wright married Landy J Bevis (1869-1947).

Landy Bevis was the son of Caroline Bevis (1842-1938), daughter of Zilla Hames (1812-1883) and William Bevis (1807-1883). (William Bevis also divorced one of more of his three wives).

Zilla Hames was the sister of Elizabeth Hames, both daughters of John M. Hames and Sarah Fowler.

As mentioned before, Ebenezer Fowler and Stephen Fowler were both on the Coroner’s Inquest Jury. Who were these two Fowler men?

Ebenezer Fowler was the son of Milly Mitchell (1811- after 1880) and Lemuel Holter Fowler (1808-1865), son of John Fowler “the Hatter” (d. 1833).

The links below will expand on the lineage of Ebenezer Fowler:

Stephen Fowler (1800-1866) was the son of Ephraim Fowler (1765-1822), son of Henry Ellis Fowler (1746-1808).

There was a military connection between William Goode Fowler, George W. Fowler, John Tipton Fowler, and Thomas Fowler and Seaborn Woolwright. They all enlisted and served together in Company D of the Holcombe Legion Cavalry.

Links below for those interested in these four Fowler men:

Bryant Fowler, born about 1824 and a son of Stephen Fowler, signed the document vouching for Louisa Eliza Comer Woolbright in her attempt to collect the money owed to her deceased soldier husband Seaborn Woolbright. Thus, I include a link for Bryant Fowler:

IN CONCLUSION

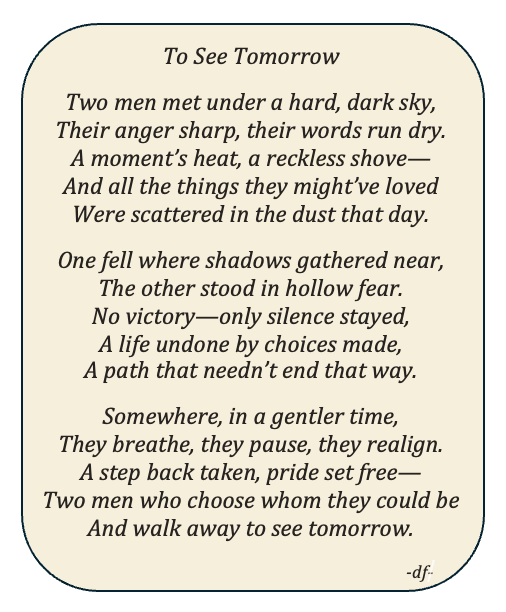

It was a turbulent time, the Civil War and the murder of Mastin Comer. Lives were turned upside down and life would never be the same because of both events.

Thousands upon thousands of men died in the war, while the murder of Maston Comer was the death of one man only. Yet, the tragedy in the Comer and Woolbright families still lingers in the minds of descendants today.

Why had this happened? Imagine if the two men — Mastin Comer and Seaborn Woolbright –had just let cross words bounce off themselves, shook hands, each man walking home to his own family.

left a voicema

LikeLike

Thank you so much for this extensive research. Seaborn Woolbright and Eliza Comer are my 3rd great-grandparents through their eldest daughter Ellen Woolbright Fowler Bullocks. You’ve cut through a few dead ends for me before for sure, including the parentage for Ellis Jackson Fowler.

I’ve not seen most of these scanned docs from the inquest into Mastin Comer’s murder – I’ve only seen summaries in previous research. I’d love to try to request higher quality scans at some point. Are those part of collection of the Union County Court, or are they in the SC Archives?

Before my great-aunt Jack Fowler Cohen passed away, I asked her if she could remember her grandmother Ellen – they all called her “Granny Bullocks” because they only really knew her after she married the second time after Ellis Jackson “Jack” Fowler died. Her one memory of her from being a little girl is that to let the girls help in the kitchen, Ellen would throw sand down on the kitchen floor to help soak up cooking grease and let the little ones help sweep it up.

LikeLike

Thanks for sharing the story of the sand on the kitchen floor! Those little memories are real treasures.

I started the draft version of this work more than two years ago (I have more than 100 articles in draft

form waiting to be finished). I will go back and send copies of those documents to your email. I do not

remember at this moment where I found them, but it would have been one of the sources you mentioned. I am

guessing that you know about the “new” AI full text on familysearch.org? It is a tool where AI scans their

millions of documents — most of which are not indexed — and gives you search results in mere seconds. I have

been able to find documents that I have spent the past decade searching for, and consequently, have knocked

down a few brick walls. Thanks, for reading and for your comments!! Deb

LikeLiked by 1 person

Deb, thanks for that tip! I’ve the AI assistant on a record, but I didn’t realize the “full text” pulled the unindexed content – I’m finding so many things already! 🙂 -Josh

LikeLiked by 1 person

LikeLike