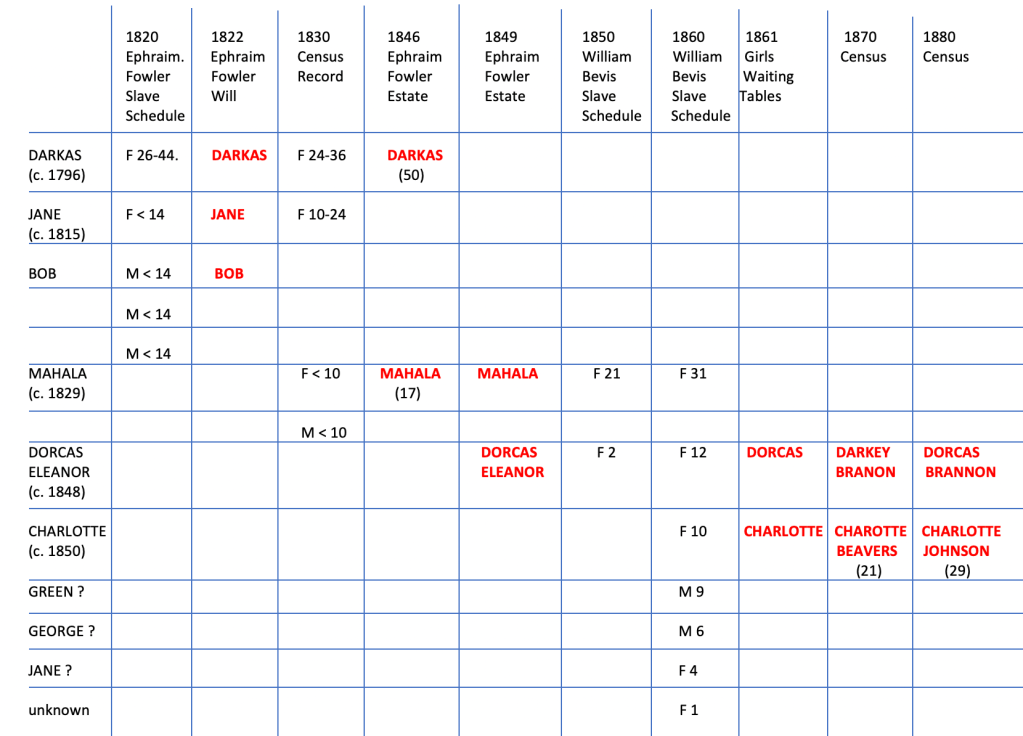

Four women — Darkas, Mahala, Dorcas Eleanor, and Charlotte — are deeply embedded in my conscious thought. They lived long ago, yet it feels like they are always with me. I cannot explain the connection that I have with these women and their descendants, but it is real.

They were the enslaved people of the Ephraim Fowler family in Union County, South Carolina.

The very first time I became aware of the existence of these enslaved women was in my research of Ephraim Fowler (b. 1765).

Ephraim Fowler had one enslaved person in his household of 1800, and one in 1810.

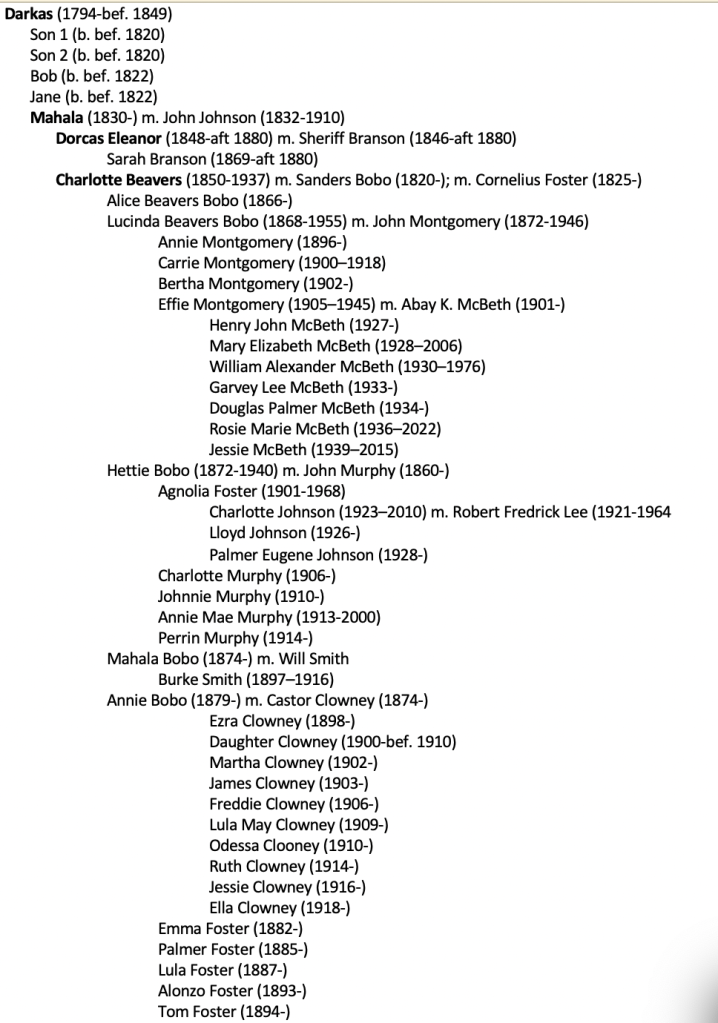

The census record of 1820 indicated that Ephraim Fowler had five enslaved people in his household: one female aged 26 to 44, one female and three males under the age of fourteen. A woman and her four children.

On the eighth day of February in 1822, Ephraim Fowler inscribed his mark — an “X” — representing his signature on his Last Will and Testament.

This document is the first evidence that I have found in my research of the name of the enslaved woman. Darkas.

“I give and bequeath to my wife Nancy Fowler my Negro woman Darkas…“

“…in that case my will is as follow that Darkas and all her children except Bob negro boy…“

“I will and bequeath to my daughter Betty one negro girl named Jane…”

Ephraim Fowler left a wife and ten children behind after his death in 1822. There is abundant evidence that allows us to trace this family to present day. But, what of the enslaved people of the household? Darkas and “all her children” and Jane and Bob?

Jane was “given” to Ephraim’s daughter Betty. This fact seems to be supported by the 1830 Union County census when Elizabeth “Betty” Fowler and husband Richardson Bentley (1814-1843) were enumerated with one enslaved female aged 10 -24. This was likely Jane.

The Richardson Bentley family moved to Blount County Alabama before the 1840 census which shows no enslaved people in the household. Jane’s fate after 1830 is unknown to me.

Ephraim’s daughter Mary “Polly” Fowler had married Richard White before 1822. The Richard White household of 1830 included an enslaved woman aged 24-36, one male and one female under the age of ten. Yes, I would be the farm that this was Darkas (estimated age 36), and two of her children: a young son and Mahala, both born between 1822 and 1830.

I find no evidence that any of the other children of Ephraim Fowler had any enslaved people in their 1830 households. I do not know what became of Bob and the two other sons.

It is only with years of research and just plain luck that I am able to follow Darkas, and some of her other children and their descendants throughout their lives into present day. I offer the following research to help her descendants understand their heritage.

Darkas was born circa 1796. I know nothing of her early years, her parents, where she was born, what her life was like. She was born into slavery, and she would die a slave. It is the knowledge that she had children who would live to see freedom which gives me hope for mankind.

There is a gap between 1822 when Darkas was mentioned by name, and 1846 when her name was next put into a document.

In 1846 — 24 years after the death of Ephraim Fowler — his heirs began the final settlement of the estate. It was this series of events in which the names Darkas, Mahala, and Dorcas Eleanor appeared.

• Previous to October 1, 1849, Lydia Fowler Hames, Stephen Fowler, and four of (deceased) John Fowler’s children, Thomas Fowler, Charity Fowler, Rebecca Fowler Burgess, and John Fowler had sold their shares of the estate to James Farr.

• Previous to October 1, 1849, Washington Fowler, son of John Fowler (deceased) sold his one fifth of one eighth share to David Gallman.

• April 4, 1846: Sarah Hames Fowler and husband John Hames sold her one eighth share of the estate to William Bevis.

• July 5, 1849: Three children of (deceased) Ellis Fowler— Mary Jane Fowler, B. Elbert Fowler, and Julia Fowler Sprouse — sold their shares to their brother Henry Richard Fowler.

• October 1, 1849: James Farr sold to William Bevis the shares that he had previously bought from Lydia Hames Fowler, Stephen Fowler, and four of the children of John Fowler.

• October 1, 1849: David Gallman sold to William Bevis the one fifth partial share that he had bought from Washington Fowler.

• October 10, 1849: Mary Fowler White sold her one eighth share to William Bevis.

• October 29, 1849: Henry Richard Fowler sold to William Bevis the one eight share that he solely owned after buying the shares of his siblings.

• November 7, 1849: Milly Fowler Millwood and husband James Millwood sold to William Bevis her one eighth share.

• November 7, 1849: Susan Fowler (daughter of Jasper) sold her one eighth share to William Bevis.

November 7, 1849 was the final date of the estate settlement. William Bevis now was sole owner. But why exactly did this mean?

Interestingly, no mention was made of land, no measure of acreage, given.

Instead, William Bevis bought human life. The document of 1846, whereas Sarah Fowler Hames and John Hames began the settlement process, indicated that the estate consisted of two negro slaves, fifty year old Dorcas, and seventeen year old Mahala.

Was fifty year old Dorcas the female slave Darkas mentioned in Ephraim’s will of 1822 and was Mahala her daughter?

The estate documents of 1849 specified that two negro slaves were being sold— Mahala and her child Dorcas Eleanor. No mention was made of the elderly Dorcas. Had Dorcas died in between the years 1846 and 1849? I think so. And Dorcas Eleanor born after the 1846 document which may explain why she was not specifically mentioned until the 1849 documents. I believe Dorcas was born in 1848.

The 1850 Union County Slave Schedule shows that William Bevis owned two mulatto slaves— a twenty one year old female (Mahala) and a two year old female (Dorcas Eleanor) The information is a good “fit” and indicates that these two slave women may have been the first that William Bevis had owned.

Mulatto is a word that describes a person of mixed white and black ancestry. Were Mahala and Dorcas Eleanor descendants of Ephraim Fowler or his sons?

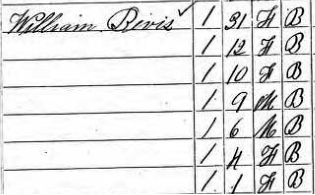

The Union County Slave Schedule of 1860 for William Bevis lists the following enslaved women and children:

- female age 31 Mahala

- female age 12 Dorcas

- female age 10 Charlotte

- male age 9

- male age 6

- female age 4

- female age 1

On July 7, 1937, Caldwell Sims of Union, SC went to the County Home and interviewed Caroline Bevis, daughter of William Bevis. The interview was later published in a book edited by Elmer Turnage. The book was a compilation of interviews of former slaves and slave owners.

Project 1885-1

FOLKLORE

Spartanburg, Dist. 4

July 26, 1937

Edited by:

Elmer Turnage

SLAVERY REMINISCENCES

“I was raised in the wood across the road about 200 yards from here. I was very mischievous. My parents were honest and were Christians. I loved them very much. My father was William Bevis, who died at the age of eighty. Miss Zelia Hames of Pea Ridge was my mother. My parents are buried at Bethlehem Methodist Church. I was brought up in Methodism and I do not know anything else. I had two brothers and four sisters. My twin sister died last April 1937. She was Fannie Holcombe. I was in bed with pneumonia at the time of her death and of course I could not go to the funeral. For a month, I was unconscious.

“When I was a little girl I played ‘Andy-over’ with a ball, in the moonlight. Later I went to parties and dances. Calico, chambric and gingham were the materials which our party dresses were made of.

“My grandmother, Mrs. Phoebe Bevis used to tell Revolutionary stories and sing songs that were sung during that period. Grandmother knew some Tories. She always told me that old Nat Gist was a Tory … that is the way he got rich.

“Hampton was elected governor the morning my mother died. Father went in his carriage to Jonesville to vote for Hampton. We all thought that Hampton was fine.

“When I was a school girl I used the blue back speller. My sweetheart’s name was Ben Harris. We went to Bethlehem to school. Jeff and Bill Harris were our teachers. I was thirteen. We went together for six years. The Confederate War commenced. He was very handsome. He had black eyes and black hair. I had seven curls on one side of my head and seven on the other. He was twenty-four when he joined the ‘Boys of Sixteen’.

“He wanted to marry me then, but father would not let us marry. He kissed me good bye and went off to Virginia. He was a picket and was killed while on duty at Mars Hill. Bill Harris was in a tent nearby and heard the shot. He brought Ben home. I went to the funeral. I have never been much in-love since then.

“I hardly ever feel sad. I did not feel especially sad during the war. I made socks, gloves and sweaters for the Confederate soldiers and also knitted for the World War soldiers. During the war, there were three looms and three shuttles in our house.

“I went often to the muster grounds at Kelton to see the soldiers drill and to flirt my curls at them. Pa always went with me to the muster field. Once he invited four recruits to dine with us. We had a delicious supper. That was before the Confederacy was paralyzed. Two darkies waited on our table that night, Dorcas and Charlotte. A fire burned in our big fireplace and a lamp hung over the table. After supper was over, we all sat around the fire in its flickering light.

“My next lover was Jess Holt and he was drowned in the Mississippi River. He was a carpenter and was building a warf on the river. He fell in and was drowned in a whirlpool.”

Source: Miss Caroline Bevis (W. 96), County Home, Union, S. C.

Interviewer: Caldwell Sims, Union, S. C. (7/13/37)

In the voice of Caroline Bevis: “Two darkies waited on our table that night, DORCAS and CHARLOTTE.”

Were these two women, Dorcas and Charlotte, the two older daughters of Mahala? Yes.

It is somewhat amazing that we are able to trace an enslaved woman named Darkas born circa 1796 and mentioned in Ephraim Fowler’s will of 1822 to a document selling her in 1846, and learning of her probable death before 1849 due to her absence in the documents of 1849.

It is equally amazing that we perhaps “know” that she had a daughter named Mahala born circa 1829 who was sold in the estate transactions of 1846 to 1849.

Even more so miraculous is that we can trace Mahala’s known daughter, Dorcas Eleanor b. 1848, through the 1849 estate documents and Mahala’s probable daughter Charlotte and the unnamed children from the 1860 Slave Schedule.

The reference of Dorcas and Charlotte in the interview that Caroline Bevis gave in 1937 allows us a rare glimpse into the lives of typically hard to trace enslaved people.

Now.

Sit down.

Not only was Caroline Bevis of Union County, SC interviewed for the Slave Narratives, BUT SO WAS CHARLOTTE!!!!!!!!!!

In Spartanburg County, Charlotte Foster was interviewed on May 28, 1937 by F.S. Dupre. It took serious research to make the leap from Charlotte Beavers (Bevis) to Charlotte Bobo to Charlotte Johnson to Charlotte Foster. Yet, here we are.

Project 1885 -1-

District #4

Spartanburg, S.C.

May 28, 1937

FOLKLORE: EX-SLAVES

Six miles east of Spartanburg on R.F.D. No. 2, the writer found Aunt Charlotte Foster, a colored woman who said she was 98 years old. Her mother was Mary Johnson and her father’s name was John Johnson. She is living with her oldest daughter, whose husband is John Montgomery.

She stated she knew all about slavery times, that she and her mother belonged to William Beavers who had a plantation right on the main road from Spartanburg to Union, that the farm was near Big Brown Creek, but she didn’t know what larger stream the creek flowed into. Her father lived on another place somewhere near Limestone. She and her mother were hands on the farm and did all kinds of hard work. She used to plow, hoe, dig and do anything the men did on the plantation. “I worked in the hot sun.” Every now and then she would get a sick headache and tell her master she had it; then he would tell her to go sit down awhile and rest until it got better.

She had a good master; he was a Christian if there ever was one. He had a wife that was fussy and mean. “I didn’t call her Mistus, I called her Minnie.” But, she quickly added, “Master was good to her, just as kind and gentle like.” When asked what was the matter with the wife, she just shook her head and did not reply. Asked if she had rather live now or during slavery times, she replied that if her master was living she would be willing to go back and live with him. “Every Sunday he would call us chilluns by name, would sit down and read the Bible to us; then he would pray. If that man ain’t in the Kingdom, then nobody’s there.”

She said her master never whipped any of the slaves, but she had heard cries and groans coming from other plantations at five o’clock in the morning where the slaves were being beaten and whipped. Asked why the slaves were being beaten, she replied rather vehemently, “Just because they wanted to beat ’em; they could do it, and they did.” She said she had seen the blood running down the backs of some slaves after they had been beaten.

One day a girl about 16 years of age came to her house and said she’d just as leave be dead as to take the beatings her master gave her, so one day she did go into the woods and eat some poison oak. “She died, too.”

On one plantation she saw an old woman who used to get so many beatings that they put a frame work around her body and ran it up into a kind of steeple and placed a bell in the steeple. “Dat woman had to go around with that bell ringing all the time.”

“I got plenty to eat in dem days, got just what the white folks ate. One day Master killed a deer, brung it in the house, and gave me some of the meat. There was plenty of deer den, plenty of wild turkeys, and wild hogs. Master told me whenever I seed a deer to holler and he would kill it.”

When slaves were freed her mother moved right away to her father’s place, but she said the two sons of her master would not give her mother anything to eat then. “Master was willing, but dem boys would not give us anything to live on, not even a little meal.”

“After the Civil War was over and the Yankee soldiers came to our place, dey just took what they wanted to eat, went into de stable and leave their poor, broken-down horses and would ride off with a good horse. They didn’t hurt anybody, but just stole all they wanted.”

One day she said her master pointed out Abe Lincoln to her. A long line of cavalry rode down the road and presently there came Abe Lincoln riding a horse, right behind them. She didn’t have much to say about Jeff Davis, except she heard the grown people talking about him. “Booker Washington? Well, he was all right trying to help the colored people and educate them. But he strutted around and didn’t do much. People ought to learn to read the Bible, but if you educate people too high it make a fool out of them. They won’t work when they gets an education, just learns how to get out of work, learns how to steal enough to keep alive. They are not taught how to work, how do you expect them to work when they ain’t taught to work? Well, I guess I would steal too before I starved to death, but I ain’t had to steal yet. No man can say he ever gave me a dollar but what I didn’t earn myself. I was taught to work and I taught my chilluns to work, but this present crowd of niggers! They won’t do.”

She stated her mother had twelve children and the log house they lived in was weatherboarded; it was much warmer in such a house during cold weather than the houses are now. “Every crack was chinked up with mud and we had lots of wood.” Her mother made all their beds, and had four double beds sitting in the room. She made the ticking first and placed the straw in the mattresses. “They beat the beds you can get now. These men make half beds, den sell ’em to you, but dey ain’t no good. Dey don’t know how to make ’em.”

Aunt Charlotte said she remembered when the stars fell. “That was something awful to see. Dey just fell in every direction. Master said to wake the chilluns up and let ’em see it. Everybody thought the world was coming to an end. We went out on de front porch to look at the sight; we’d get scared and go back into de house, den come out again to see the sight. It was something awful, but I sure saw it.” (Records show that the great falling of stars happened in the year 1833, so Aunt Charlotte must be older than she claims, if she saw this eventful sight. Yet she was positive she had seen the stars falling all over the heavens. She made a sweep of her arm from high to low to illustrate how they fell.)

Source: Aunt Charlotte Foster, RFD #2, Spartanburg, S.C.

Interviewer: F.S. DuPre, Spartanburg, S.C.

William “Bevis” was William “Beavers”and William “Beavis” in legal documents. The misspelling of names in the 1800s was common.

William Bevis (Beavers) lived near Big Browns Creek in the Kelton/Pearidge part of Union County, SC.

Zilla Hames — wife of William Bevis, daughter of Sarah Fowler Hames, granddaughter of Ephraim Fowler — would have been the mistress who was “fussy and mean”. That one sentence gives us a glimpse of Zilla’s character.

Unlike his wife and sons, William Bevis seemed to be a kind, compassionate Christian gentleman.

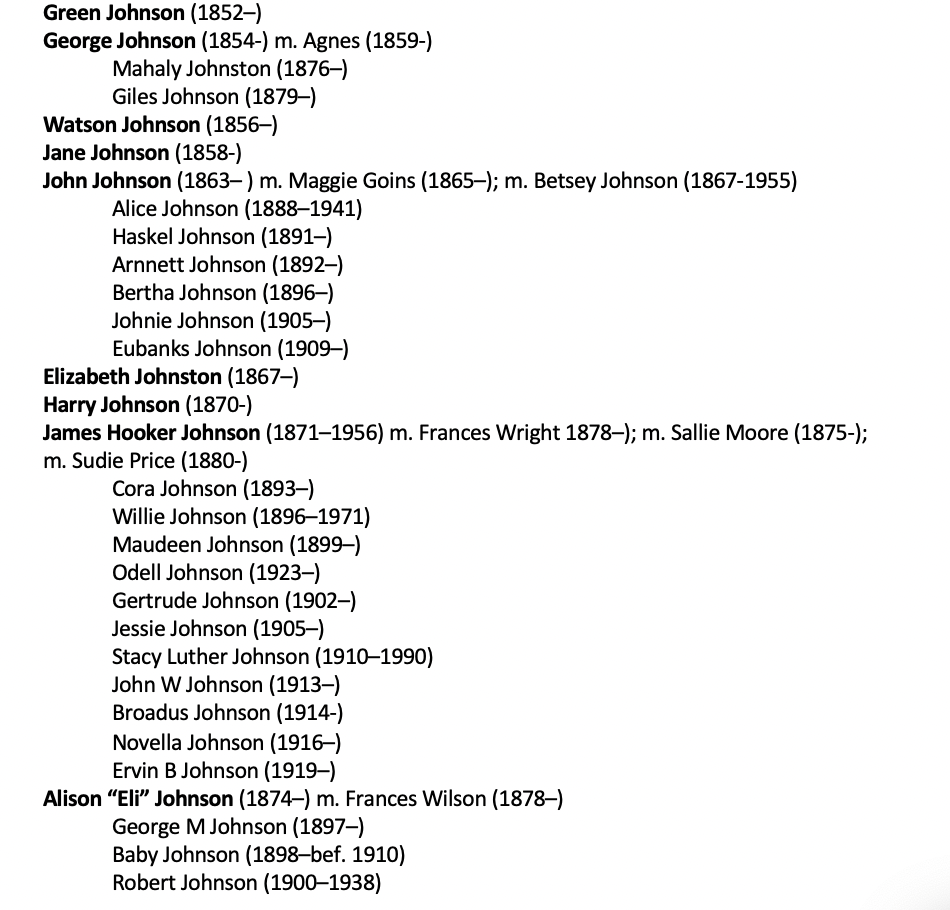

Charlotte’s mother was Mahala (not Mary), and her father (or stepfather) was John Johnson. Her oldest living daughter was Lucinda Beavers Bobo married to John Montgomery.

In the 1870 Union County census, William Beavis, wife Zillah Hames Beavis, daughters Caroline and Amanda Beavis were living only four households away from Charlotte Beavers, age 21 and black. Was this Charlotte, daughter of Mahala? Yes.

Former slaves often took the surnames of the men who owned them. It is not a far stretch of the imagination to assume that the Charlotte Beavers living near the William Beavis family was the former slave of the Bevis family.

Twenty-one year old Charlotte Beavers was in the household with Sandy Beavers (age 60). There were two daughters, Alice Beavers (age 4) and Lucinda Beavers (age 2).

Next door to this family was the Scheriff Branon (age 24) family. His wife was Darkey (age 23). There was one year-old Sarah Branon.

Sit down. Darkey Branon was Dorcas Eleanor, daughter of Mahala, granddaughter of Darkas.

Next household– Jane Gault (age 30 and mulatto). Jane had four young sons in her household. I have not specifically identified her as a descendant of Darkas but I am working on it. It is my thinking that this Jane was named after the Jane of the 1822 Last Will and Testament.

Where was Mahala in 1870? Mahala was married and living in nearby Goudeysville which was part of Union County until the late 1890s.

Mahala (listed as age 45 and mulatto) had married John Johnson (age 46) and they had seven children in their 1870 household.

John Johnson was found in the 1860 census as a free black man, living in the Andrew McNease household and working as a carpenter. The McNease family and the William Bevis family were neighbors in the Pinckney area of Union County so it is not difficult to see how Mahala and John Johnson met.

During the next decade, these families relocated to the Broad River in York County. As the crow flies, it was really only a short distance away.

In 1880, the census gives up great information. There was a young mulatto man named Noah Lockard, his wife Adeline, and three children living next to our Mahala. I am still working to see if I can connect these families.

John Johnson, Mahala, her daughter Charlotte (Beavers/now Johnson), and four other Johnson children were in the 1880 household. There were five granddaughters as well:

- Alice Bobo (previously Alice Beavers)

- Lucinda Bobo (previously Lucinda Beavers)

- Hetty Bobo

- Mahaley Bobo

- Cooley Bobo

These five granddaughters were the children of Charlotte and Sandy Beavers. In-depth research proved that the elder Sandy Beavers was Sanders Bobo. He was likely given the surname “Beavers” in 1870 by some indifferent census taker.

Briefly, Sanders Bobo was born ca. 1810 and died after 1870. His first wife was

Dianah Sharp. Their known children were Julia Bobo (1848-1918), Mary “May” Sharp Bobo, and Henry Bobo.

The Sheriff Brannon family (notice the different spelling from the 1870 document; same indifferent census taker) lived next door to the John and Mahala Johnson family. Dorcas (Eleanor) was 32 years old, her husband Sheriff was 33 years old, and daughter Sarah was eleven. George Johnson (age 24) was a brother of Dorcas and in the same household with his wife Agnes, son Giles, and daughter Mahaly. My heart is overjoyed to see the name Mahala pass down through the generations.

The following chart may help show the lines and documentation I used to research a family as they went from a life of enslavement to freedom.

Yes, I have traced the descendants of Darkas to present day. There are many men, women, and children walking the earth today — who live far away and not so far away — who would not be here had not Darkas lived over two hundred years ago.

They, perhaps, do not know of her, their enslaved ancestor. I have hope that some of them will find me and that Darkas, Mahala, Dorcas Eleanor, and Charlotte will find their way out of the darkness into the hearts of the ones who carry her in their blood.

What great research! Thank you for all you do to document the Fowler family. I can’t tell you how much I have learned from your research. Keep up the good work!

LikeLike

Thanks Lisa! I have not posted a lot this year — too busy with my real job! But I have a little time off and hope to get more on line in the next few weeks.

LikeLike

Hello, my great great great grandfather is Emanuel Fowler. I feel like he is somehow tied in to Darkas, Mahala, Dorcas, and Charlotte. I can’t figure out who Emanuel’s parents are, if you could offer any insight or information I would be extremely grateful, thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Jalen, Please email me at debfowler@aol.com. I am very interested in your Fowler line and will help with Emanuel.

Deb

LikeLike

Hi Jalen, I have just taken a look at your Emanuel Fowler. I have had him on my genealogy radar for a very long time. I have reason to believe that he is a descendant of Henry Ellis Fowler. This can be proven if you are interested in finding out. I also believe that you are likely related to Darkas, Mahala, Dorcas Eleanor and Charlotte. I am happy to help you with your family. Please email if you want to pursue your family history in depth. I am so glad that you found my site!

LikeLike