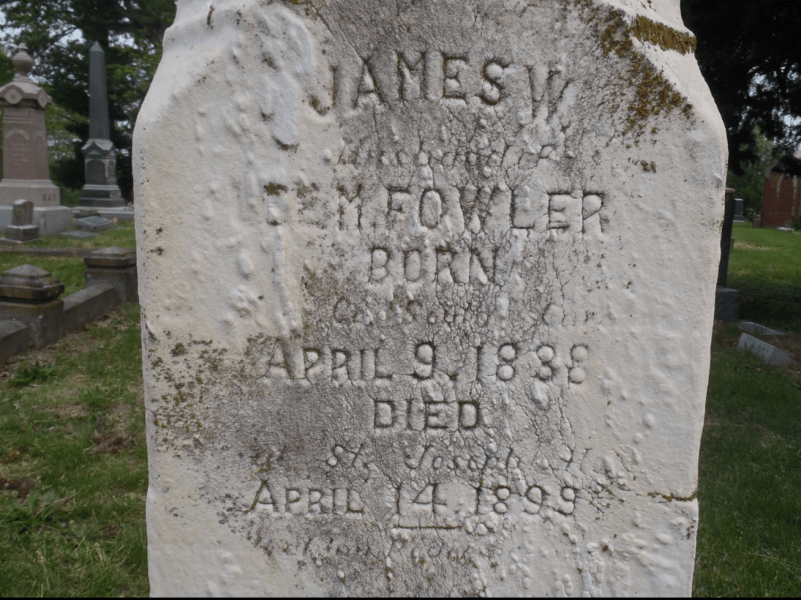

James W. Fowler was born April 9, 1838 in Union County, South Carolina. He was a son of James Fowler (1793–1858) and Susan Gault (b. 1800). As a grandson of Godfrey Fowler (1773–1850) and Nancy "Nannie" Kelly (1775–1857), James W. Fowler came from a family of military men. His grandfather Godfrey Fowler fought in the…

JAMES W. FOWLER (1838-1899) Son of James, Grandson of Godfrey